Most authors I know will admit to the obscene satisfaction derived from creating a really good villain. Unshackled from the bonds of goodness or morality, it’s often alarmingly exciting to find that the really wicked characters have a habit of creating themselves on your page or screen. They simply stroll into your head fully formed and ready for mayhem.

It’s especially shocking when that character is female.

Perhaps it’s the joy of toppling the order of things? After all, aren’t women – at heart – supposed to be empathetic, nurturing, loving and kind? Yes, they can be clever, sparky and opinionated; they can even be that most toe-curling of words ‘feisty’, but how often are they allowed to be truly, diabolically bad?

Despite years of emancipation, there’s still a whiff of sulphur about a woman who’s gone to the dark side. And there’s certainly judgement. Females who step beyond the bounds of good behaviour are regarded with more horror and even perhaps with disgust than bad men because their very existence is a threat. Whisper it, but in their rebellion against the domestic and maternal realm, wicked women are unsettling and unnatural.

It’s enraging that male villains in books frequently get to grandstand and just ‘be’ without too much sensitive exploration of their backstory, while their distaff counterparts must always have suffered terribly at some point in their past – because that’s the only way such an abomination of nature could possibly have come to be.

No writer should even look at anything on Goodreads, but it’s like Pandora’s Box. The temptation to look at reader reviews – not just of your own books – is like a Siren luring you to the crashing rocks of disappointment. Quite often I’ll love a fellow author’s wicked character, but I’ll be amazed to discover that others didn’t share my enthusiasm. All too frequently, people struggle with a book because the main female character made them feel ‘uncomfortable’, or worse they couldn’t ‘sympathise’ with her.

I don’t think Shakespeare wanted us to sympathise with Lady Macbeth, but, oh boy (or should that be ‘oh girl’?) do we remember her!

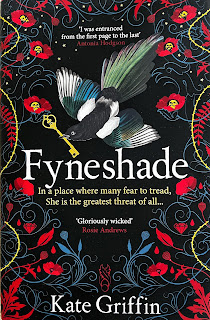

In my new neo-Victorian Gothic novel, anti-heroine Marta is wicked to the core. There’s little point in combing through her past to find compelling reasons for her transgressive nature. She was born that way.

Rightly suspected of seducing the son of the local vicar, Marta is sent (banished more like) to Fyneshade, an ancient crumbling medieval house where she is to take up the role of governess to the owner’s motherless daughter. The usual convention of the Gothic novel sees a good girl sent to a terrible nightmarish place, but here Marta brings the darkness with her.

I hope she’s memorable in the best and worst possible ways. As Margaret Atwood rightly says: “Create a flawless character and you create an insufferable one.”

I’m here to stand up for horrible heroines who are just completely themselves. These are some of my favourites.

Becky Sharp: Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray. Oh Becky! How do I love thee – let me count the ways. For a start, when I first read this stupendous novel at the age of 13, I’d never come across a central female character in ‘literature’ who was so deliciously wicked. Becky is basically a charming, clever, beautiful, talented psychopath desperate to rise in society. We know she’s ruthlessly bad to the bone but she is also utterly bewitching, and readers find themselves rooting for her despite their better natures.

Rebecca: Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. It’s odd that the woman who is dead before the novel even starts becomes such a vividly wicked presence throughout. Although the unnamed heroine of the tale is a mouse-like ingenue, very much in the classic Gothic mode, her haunting predecessor – the former wife of Max de Winter – is the dark star around which all things revolve. Rebecca is gradually revealed as a cool, brittle and heartless seductress whose flame is lovingly tended by her former lady’s maid, Mrs Danvers. Rebecca offers the joy of two exceptional anti-heroines for the price of one.

Amy Dunne: Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. Here we have the bad girl as the ultimate unreliable narrator. We explore the mysterious disappearance of Amy through the first-person account of her husband, Nick, and, initially, through Amy’s own diary entries. It’s clear that nothing is quite what is seems, but it’s only when the reader reaches the second half of the book that Amy’s shocking, perfectly plotted wickedness is revealed. She’s not only bad, she’s brilliant and although we may not like her, we can only admire the cool precision of her evil genius. Amazing Amy indeed.

Scarlett O’Hara: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell. I’ll be upfront - this novel has not aged well. With its disturbingly casual racism and rose-tinted vision of America’s brutal deep Southern past it is a difficult read today, but, but… In the character of Scarlett Mitchell created an unforgettable anti-heroine and perhaps set the template for countless fascinatingly amoral, unlikeable females in books. Spoiled, vain and ruthlessly calculating, Scarlet will do anything to get what she wants. Her badness rips through the pages like the Great Fire of Atlanta.

The Marquise de Merteuil: Dangerous Liaisons by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. I’ll hazard a guess that although they’re familiar with the film, a lot of people haven’t read this epistolary novel of 1782 - and that’s a pity as it’s quite the page-turner. I came across it at university when it was part of the ‘Development of the European Novel’ course and I immediately fell under the spell of the beautiful, cunning, jealous, spiteful and utterly deadly Marquis whose weapon of choice is sex.

Barbara: Notes on a Scandal by Zoë Heller. Oh my, this is a creepy read. The affair between attractive youngish pottery teacher Sheba and her fifteen-year-old pupil Steven is bad enough, but the predatory, obsessional interest of the aptly named Barbara Covett - the older teacher to whom Sheba confesses - is the stuff of nightmare.Barbara takes it upon herself to record the details of the affair and even uses gold stars to highlight key events. “This is not a story about me,” she says but actually the more she writes about Sheba, the more we learn about Barbara, and it’s quietly, claustrophobically horrifying.

Beatrice: Wideacre by Phillipa Gregory. Before the Other Boleyn Girl, there was Wideacre, the 1987 debut by Philippa Gregory, and what a sumptuously decadent and wicked brew it was. Beatrice Lacey is the daughter of the Squire of Wideacre. At five years old she falls passionately in love with her father’s estate and decides to stay there for ever. But her dreams are shattered when she learns that her brother, absent Harry, will inherit. Wilful, wicked, sexy, amoral and ravishingly untouched by anything approaching a conscience, bad beauty Beatrice will do anything to make sure she keeps Wideacre. I love her. This review from the dreaded Goodreads tells you everything you need to know:

“I absolutely hated this book… The heroine is despicable in every possible way, yet the author clearly expects you to root for her à la Scarlett O’Hara. She commits multiple acts of murder, participates in very creepy incest, and betrays people who love her. I’m not particularly squeamish, but I do require some redeeming qualities in a protagonist if I’m to forgive them all that, and Gregory didn’t provide them.”

Fyneshade is by Kate Griffin (Viper Books) Out Now

Many would find much to fear in Fyneshade's dark and crumbling corridors, its unseen master and silent servants. But not I. For they have far more to fear from me... On the day of her beloved grandmother's funeral, Marta discovers that she is to become governess to the young daughter of Sir William Pritchard. Separated from her lover and discarded by her family, Marta has no choice but to journey to Pritchard's ancient and crumbling house, Fyneshade, in the wilds of Derbyshire.

All is not well at Fyneshade. Marta's pupil, little Grace, can be taught nothing, and Marta takes no comfort from the silent servants who will not meet her eye. More intriguing is that Sir William is mysteriously absent, and his son and heir Vaughan is forbidden to enter the house. Marta finds herself drawn to Vaughan, despite the warnings of the housekeeper that he is a danger to all around him. But Marta is no innocent to be preyed upon. Guided by the dark gift taught to her by her grandmother, she has made her own plans. And it will take more than a family riven by murderous secrets to stop her...

No comments:

Post a Comment