Job: -

Author

Website:

https//jakelamar.com

X:

@jakelamar

Introduction

Jake Lamar is an author of a memoir, seven novels and numerous essays, reviews, and short stories. His novel The Last Integrationist won France’s Grand Prize for best foreign thriller. His most recent book Viper’s Dream was a New York Times top 4 thriller of the month. It was one of The Guardian’s best thrillers of 2023 and is currently shortlisted for the CWA Historical Dagger 2024

Current book?

I am writing a crime novel about chess. I describe it as a cross between Stefan Zweig and Chester Himes.

Favourite

book?

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller. Read it when I was fourteen. It was the first time I really understood satire. That Heller could describe the horrors of war in such a darkly humorous way was a revelation for me.

Which two

musicians would you invite to dinner and why?

John Lennon and Paul McCartney in their 1966 incarnations. This is the toughest question in the bunch for me. Because some of the musicians I revere most might not make the greatest dinner party company. Billie Holiday would show up hours late. Thelonious Monk would probably just glower benignly, hardly speaking at all. Miles Davis might insult the other guests. Lennon and McCartney might very well insult the other guests but hearing them riff off each other would more than make up for it.

How do

you relax?

Just hanging out with Dorli, my partner of 28 years. A very wise, older friend of mine once said: "The most important thing isn't having someone to do something with. It's having someone to do nothing with."

Which

book do you wish you had written and why?

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. Read it when I was fifteen. An astounding literary feat on so many levels. Veering from tragedy to satire, the novel encompasses the madness of the USA's racial caste system, from the rural South to the urban North. Ellison gave the world a metaphor for social marginalization---invisibility---that resonates with people to this day, as when groups and individuals say they want "to be seen." And, amazingly, in this 500-plus page epic, the reader never learns the name of the first-person narrator.

What

would you say to your younger self of you were just starting out as a writer?

Writing and Publishing are two different planets. You will live on Planet Writing. Every once in a while, you will get in your spacecraft and fly over to Planet Publishing. But you will live on Planet Writing. Never let the volatile climate on Planet Publishing negatively impact the atmosphere on Planet Writing.

How would

you describe your latest published book?

My friend and colleague David Peace was the first to call Viper's Dream "jazz noir." I think that nails it. The book is a hard-boiled crime novel---in the tradition of Hammett, Chandler, and Himes---set in the jazz world of Harlem between 1936 and 1961.

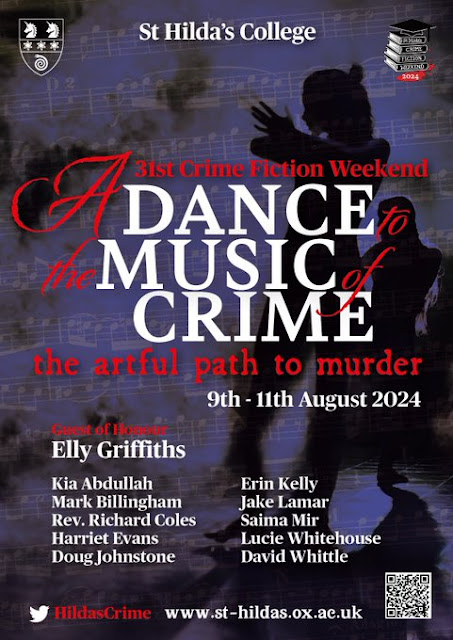

With A

Dance to the Music of Crime: the artful crime to murder being the theme at St

Hilda's this year, which are you three favourite albums?

Kind of

Blue by Miles Davis

Monk's

Dream by Thelonious Monk

Purple Rain by Prince

If you

were given the ability to join a band which, would it be and why?

Sly and the Family Stone, circa 1969. The music of my late childhood/early adolescence, naturally. Check them out in the magnificent concert documentary film Summer of Soul. A band made up of men and women, of different ethnic origins, mixing gospel, rhythm-and-blues, jazz and soul, to create the ultimate feel-good Funk.

If you were to re-attend a concert which, would it be and why?

Easiest question in the bunch. Prince: The Fox Theatre; Detroit, Michigan; April 1993. A relatively intimate venue---5,000 seats---not an arena or stadium. His Purple Majesty was at the peak of his powers. The crowd was 75% African American. By the third hour, the place was delirious. Prince screamed from the stage: "I got too many HITS! Y'all can't STAND it!"

What are

you looking forward to at St Hilda’s?

The

conversations!

A hard-boiled crime novel set in the jazz world of Harlem between 1936 and 1961, Viper's Dream combines elements of the epic Godfather films and the detective novels of Chester Himes to tell the story of one of the most respected and feared Black gangsters in America. At the centre of Viper's Dream is a turbulent love story. And the climax bears an element of Greek tragedy. For the better part of 20 years, Clyde 'The Viper' Morton has been in love with Yolanda 'Yo-Yo' DeVray, a singer of immense talent but a woman consumed by demons. By turns ambitious and self-destructive, conniving and naive, Yo-Yo is a classic femme fatale. She is a bright star in a constellation of compelling characters including the chauffeur-turned-gangster Peewee Robinson, the Jewish kingpin Abraham 'Mr. O' Orlinsky, the heroin dealer West Indian Charlie, the corrupt cop Red Carney, the wife-beating singer Pretty Paul Baxter, the pimp Buttercup Jones and the brutal enforcer Randall Country Johnson. But Viper's Dream has a fast-paced vibe all its own, a story charged with suspense, intrigue and plot twists and spiced with violence and humour. It is also steeped in music. The Viper's story is intertwined with the history of jazz over a quarter century.

Information about 2024 St Hilda's College Crime

Fiction Weekend and how to book tickets can be found here.

%20(2).jpg)

.jpg)