Disclaimer

The more astute among you will have realised that this month’s Getting Away With Murder is not in its usual place. This is due to the main website having been hi-jacked by interweb pirates (probably Russian) and sailed into the Bermuda Triangle, or whatever it is happens in these cases. As you may have gathered, I am no expert when it comes to modern technology, but those who claim to be assure me that normal service will soon be resumed.

In the meantime, following an untraceable transfer to a Swiss bank, I have managed to insert myself into the Shotsmag Confidential ‘blogspot’ which is normally curated by the voluptuous Ayo Onatade. She, naturally, has absolutely no responsibility for what follows unless of course legal action ensues, in which case she does.

Why We Read Crime Fiction

The Italian literary magazine Scritture migranti kindly answers that perennial question thus: Thanks to its transnational circulation and its aptitude to highlight social and political issues throughout the lens of the investigation, crime fiction offers a privileged perspective through which to observe the encounters and the conflicts associated with social and cultural mobility. Moreover, the critical reflections on the connections between social norms and otherness expressed in crime fiction encourage also to take into consideration the mobility of the genre itself in terms of genre-blending.

Who knew?

Meanderings

I suspect there are few people alive who have actually read William Le Quex’s The Invasion of 1910, though many a fan of spy fiction will have seen it referred to and it is said to have sold a million copies when published in 1906, after serialisation in, unsurprisingly, the Daily Mail.

It appeared at a time of ‘spy mania’ (probably whipped up by the Daily Mail) when the entire nation was convinced that an invasion from Europe - first from the French, then the Germans - was imminent. Can you imagine anyone getting that worked up about Europe these days?

Le Quex, a journalist, knew how to spin a scare story and his books certainly touched a nerve. The Invasion of 1910 described a successful German landing on the coast of East Anglia, their troops spearheaded by battalions of much feared Uhlans (light cavalry) leading the advance on London.

Fortunately, the vanguard of the Uhlans stopped off in Saxmundham “to refresh themselves at The Bell” and after sampling strong Suffolk Ale, the invasion naturally faltered and the invaders were eventually defeated. I do not know if there is a memorial plaque in The Bell, but as soon as I am allowed, I intend to find out.

In the book, the mayor of London issues a proclamation declaring a state of emergency and calling all loyal citizens to arms. It is dated 3rd September 1910, a date which, 29 years later, would see a similar declaration against Germany. Coincidence? Almost certainly.

*

Another example of meandering visitors to East Anglia came to mind with news of the death of the Duke of Edinburgh. In the late 1940s and early ’50s, Prince Philip, a keen cricketer, would often turn out to play for a village team organised by Pip Youngman Carter, the husband of crime writer Margery Allingham, at their home in Tolleshunt D’Arcy in Essex. (Carter was a friend of the Duke and I believe he was a guest at the Royal Wedding in 1947, though Margery was not.)

Local legend has it that no matter how many he times he drove himself from London to D’Arcy, he always got lost and had to stop at numerous public houses to ask directions, disturbing many a pub landlord early in the morning, well before opening time, though all were proud to help with the Duke’s navigation.

During the saturation media coverage of his death I began to think that I was the only person in the country who had not been asked to recount their memories of meeting him, though I can only claim that honour twice. Once was at the Brewing Research Foundation in Surrey where he extolled the virtues of British ale (admittedly to a partisan audience) and then added some rather disparaging remarks (very well received) about a certain lager brewed in Copenhagen. He said he was allowed to say such things, because he had once held a Danish passport.

*

Quite by accident, whilst perusing the jolly old interweb, I was reminded of another East Anglian connection from days of yore, in the title of a thriller which has stayed with me forty years after forgetting just about everything about its plot.

That thriller was Teeth For The Brigadier, a Sphere paperback originalpublished in 1976, and supposedly the first in a series code-named ‘Shalom’ which was never to materialise.

In truth, I remember the author far more than the book. Michael Hamilton, always known as Steve in real life, was a near neighbour of mine when I moved to the Essex village of Wivenhoe in Essex in 1975 (the painter Francis Bacon and the journalist Peregrine Worsthorne were other neighbours). He was working as a news reporter and editor on the then new commercial radio station, Radio Orwell and after several late night discussions, probably on licensed premises, I discovered that he had served during WWII in the RAF regiment and had been present at the liberation of Belsen concentration camp.

He had married a Holocaust survivor and when he had felt the need to write a thriller, as many journalists do, it had to be about an Israeli intelligence unit (‘Shalom’) tracking down and eliminating Nazi war criminals. Teeth For the Brigadier, which involved a set of false teeth as I vaguely recall, was, he told me, the first in a six-book deal, but Steve died very soon after publication of his debut and the series came to an abrupt end.

Fresh Blood

I was cheered by the news that The Piper’s Dance, the new novel by my old conspirator-in-arms Maxim ‘Murder One’ Jakubowski is to be published by Telos in July. It is not, however, a crime novel, but a ‘phantasmagorical improvisation’ on what happened to the children who followed the Pied Piper of Hamelin to their musical fate.

It is something of a departure for Maxim, the new Chairman of the CWA, who has written and edited scores of books across various genres from sci-fi to erotic thrillers, and the news was also slightly chastening as I realised that it was now 25 years since he and I co-edited the first Fresh Blood anthology showcasing new British crime writers, including Ian Rankin, John Harvey, Mark Timlin, Denise Danks and Stella Duffy.

The anthology was a spin-off of the Fresh Blood group, an ad hoc and undisciplined alliance of writers which had emerged some five years earlier in 1991 and the name came at the suggestion of the late Michael Dibdin who then claimed he ‘didn’t do short stories’ and so was, ironically, not included in the collection.

Nihil Nove Sub Sole

If one believes publishers’ hype, and one never should unless it’s about one’s own books, then there is a new and radical trend for the crime novel for ‘psychological’ suspense in a domestic setting. This usually involves a young woman who conceals a secret (about her origins, or a mental condition) and/or discovers she cannot trust her husband/partner/best friend or (surprise, surprise) a total stranger she has befriended on ‘social media’.

It isn’t of course a new trend and one of the pioneers was American Vera Caspary (1899-1987) who is best remembered for two novels, Laura (and the classic Hollywood film noir made from it) in 1942 and Bedelia in 1945.

Although set in 1913, the Bedelia of the title strikes a more contemporary femme fatale pose on the covers of both the American (left) and British paperback editions. The US cover image proved particularly popular in France where, just to ram home the point, the French edition also had Femmes Fatale in bold type on the cover, and I believe it to be still in print to this day.

Odds & Sods

Veteran thriller writer Derek Robinson, the author of many fine novels of war-in-the-air and espionage has of late begun to collect notes and jottings made during a fifty-year writing career and publish them himself under the imprint Whistle Books.

His second collection, Odds & Sods Mk 2, is now available and although the bulk of the entries concern military matters and WWII (from the role of paratroopers and gliders to the London Blitz and the bridge on the River Kwai), Robinson’s musings encompass Dylan Thomas, John F. Kennedy, T.E. Lawrence, rugby union, the role of the King’s Champion and epilepsy.

It is a fascinating collection of, well, odds and sods, especially if you have an interest in military history, and worth the price of admission if only for the warning: ‘Writers are not exemplary citizens. They steal ideas, seduce other men’s wives, borrow money, fail meet deadlines, get drunk and insult their critics. You wouldn’t want your offspring to marry one.’

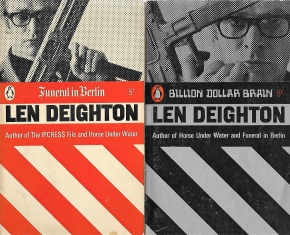

Deighton Updated

I hear from an excited American reader - though I have not seen them myself - that some of Len Deighton’s early thrillers have appeared in new editions which pay homage to the iconic paperback cover designs of the 1960s. Certainly the new editions, now published as Penguin Modern Classics (not before time) seem to bear this out:

I am not, however, tempted to replace my original copies which I have owned for more than fifty years.

The Intro Has Landed

As editor of the Top Notch Thrillers imprint for ten years, I managed to revive a hundred British thrillers from the 1960s and ’70s which had slipped out-of-print, but I never had the chance to produce a new edition of a Jack Higgins novel as they always seemed to be in print, even half-a-century on. However, I have now been given the chance to do the next best thing and write the Introduction to a new compendium volume, Graveyard To Hell, which will be published by HarperCollins in August which combines three early Higgins novels.

Known collectively as the ‘Nick Miller trilogy’, The Graveyard Shift, Brought in Dead and Hell is Always Today, are perhaps among the least well-known titles in Higgins’ prolific output and the most unusual in that he moved (temporarily) away from action/adventure thrillers set in exotic foreign locations, to try his hand at gritty murder mysteries with Nick Miller, a young police detective, as hero. Being Jack Higgins, though, the action is fast and furious and one of the books in the trilogy, Brought in Dead, is a full-blooded (and really quite impressive) revenge thriller.

First published between 1965 and 1968, they are very much of their time, but no less interesting for that. They have a toughness - Miller patrols a grim urban world of seedy night clubs, local gangsters, canals, drug addicts, telephone boxes and sex workers - which may have come as a shock to television viewers brought up on Dixon of Dock Greenand Gideon’s Way and who were not yet comfortable with Z-Cars. In 1968, Britain may not have been ready for The Sweeney, but the Nick Miller books can be seen in many ways as a sneak preview of things to come. After only three outings, Jack Higgins put Nick Miller on hold and moved on to action thrillers and war stories which would put him in the Alistair MacLean bracket. Seven years later, the eagle landed for Mr Higgins and the rest, as they say, is history.

Comfort Reading

The recent farcical attempts to tempt away our best football clubs (and Spurs, for goodness sake!) into a European Super League saw loyal, traditional supporters dismissed as ‘legacy fans’ more concerned with the past than a bright, commercial future. It made me realise that I must be a ‘legacy reader’ when it comes to crime and thriller fiction, certainly when reading for personal pleasure and comfort during the latest lockdown.

I appreciate that the never-ebbing tide of ‘domestic noir’ novels of ‘psychological suspense’ which seem to dominate publishing at the moment (see earlier rant), are not aimed at me and they may well attract new readers to the genre, but I find many of them pale and unconvincing when compared to the chillers of Ruth Rendell or Margaret Yorke. In the past I have referenced - and probably misquoted - that erudite American critic Sarah Weinman, and will do so again, when she said that most of this new wave of novels of domestic suspense contain female protagonists who are ‘either too stupid to die or batshit crazy’.

Which proves little other than I prefer my domestic noir done by ‘legacy authors’ and for comfort reading this month, I picked a ‘legacy’ thriller writer to whom I never paid sufficient attention in his heyday in the 1960s.

A Dragon For Christmas, first published in 1963, was the third of Gavin Black’s thrillers to feature hero Paul Harris, but actually the author’s fourteenth novel. Under his real name, Oswald Wynd (1918-1998), he began writing fiction shortly after the end of WW2, most of his books being set in the Far East.

Born in Japan to Scottish missionary parents, Oswald Wynd was educated in America and at Edinburgh University. Joining the Scots Guards on the outbreak of war, his fluency in Japanese earned him a commission in the Intelligence Corps and a posting to Malaya. During the Japanese invasion of 1942, he was captured and spent three years as a prisoner of war, working in the Hokkaido coal mines. After a string of romantic and historical novels, he turned, under the name Gavin Black, to the thriller in 1961, creating Paul Harris, a Singapore-based businessman, enthusiastic womanizer, suspected gun-runner and occasional undercover agent who was to feature in a series of thirteen books up to 1979.

The Paul Harris adventures were credibly-plotted thrillers, with our hero constantly under threat, but often reluctant to take violent action to save himself. In A Dragon For Christmas, Harris is in Peking on a trade visit (supposedly) selling a marine engine to the Chinese communist government and has hardly got his toothbrush unpacked before there’s a dead body planted in his hotel room (bugged, of course) and a sniper taking pot-shots at him and his only ally turns out to be a fellow Japanese ‘businessman’.

But in all fairness, one didn’t read Gavin Black for edge-of-the-seat violent action or plots which might mean the end of the world, but for his insight into - and clear affection for - the Far East. His description of a Chinese economy, going through Chairman Mao’s failing ‘Great Stride Forward’ programme must have been fascinating in 1963 and cleverly presaged some of the horrors to come in the Cultural Revolution. Most of Black’s scorn is reserved for robotic officials with a Stalinist devotion to the communist party, pointing out that all party members are equal but some are clearly more equal than others.

As a foreign, ‘imperialist’ white man’s view of the East, the language may not, today, be politically correct enough for some, though cringeworthy examples are few and far between, often affectionate (or patronising if you prefer) and usually refer to the Japanese, as when Harris ruminates: ‘A Japanese can never disguise the fact that he is lit [drunk], and they don’t really try’.

Books of the Month

Tom Bradby’s new novel Triple Cross [Bantam] is the final part of his trilogy to feature senior MI6 operative Kate Henderson and her family (and the family connection here is an important one) and can certainly be read as a piece of first-rate stand-alone spy fiction, but I would strongly suggest reading the earlier volumes - Secret Service and Double Agent - in order to get a full appreciation of the rich tapestry of both political and domestic treachery Bradby has woven.

MI6 has a Russian mole (when didn’t it?), the Prime Minister (a strangely familiar character) is being smeared with lurid sex scandals and Kate Henderson, now out of the secret service and enmeshed in multiple domestic problems, has to follow a very thin trail of breadcrumbs to uncover the mole, code-named Dante, in order to clear the PM and, possibly, salvage her marriage. The action flits from England to France, to Istanbul, Prague and Moscow, climaxing in a desperate charge for the border with Georgia, all of which makes one long for the lifting of Covid travel restrictions.

Triple Cross, indeed the complete trilogy, is highly recommended and although I cannot resist the urge to boast that I correctly guessed the identity of ‘Dante’, I have to admit I only did so 85% of the way through the third book.

Just when you thought Covid was a thing of the past (okay, I’m getting ahead of myself, but bear with me), Frank Gardner’s third thriller Outbreak [Bantam] threatens us, post-Covid, with a totally lethal outbreak of a man-made virus which will, in the hands of right-wing neo-Nazi nut-jobs, ‘cleanse’ the non-Aryan world by recreating the bubonic plague.

MI6 agent Luke Carlton has to discover the origin of the virus and then, with the help of traditional enemies within Russia’s GRU has to infiltrate the neo-Nazi group via modern communications technology (a lot of phones are involved in this rather than shoe leather, as Quiller had to do it in Berlin in 1965). Carlton also spends an exhausting time on aeroplanes, flitting from London to Svarlbad, to Vilnius in Lithuania, to Moscow and back for a gripping climax in, of all places, Braintree in Essex.

Carlton is no James Bond and has a slight touch of the Boy Scout about him at times, but Frank Gardner puts him through the mill in a story right out of the Frederick Forsyth playbook when it comes to driving the plot at a ferocious pace. Along the way, Gardner packs in the detail of international espionage and trade-craft, all of which rings completely true, as you might expected from the BBC’s veteran security correspondent. When he tells me that the GRU’s training academy is known as ‘The Conservatory’ and is situated at 50, Narodnoe Opolchenie Street in Moscow, I believe him implicitly. I was also delighted to learn that MI6 in-house slang for their sister agency MI5 is ‘Snuffbox’.

I only discovered Kent police detective Alex(andra) Cupidi last year but she immediately shot into my premier league of favourite fictional sleuths. As created by William Shaw, she features in a new novel, The Trawlerman [Riverrun], suffering PSTD from her last case and is, in theory, on sick leave, left to prowl (mostly by bicycle) the wild wastes of Dungeness.

Naturally, Alex cannot keep her investigative nose out of the many shady dealings on her patch which seem to happen right under it, including a Folkestone trawlerman who went missing at sea seven years before, a recent brutal double murder, a financial scam which has wiped out the savings of a friend, a cross-Channel drugs trade and an army veteran gone feral in the local woods. Whilst also dealing with a truculent teenage daughter and suffering stress-related nightmares and premonitions, Alex finds the best therapy is to tackle crime even if she has to do so unofficially.

Cleverly plotted, reeking of a desolate Kentish coastline where the main tourist attraction is a nuclear power station, and with a resourceful, fully-rounded (and flawed) protagonist, The Trawlerman is an excellent, totally absorbing crime novel which can only augment the reputations of William Shaw and Alex Cupidi.

Lector intende - laetaberis (‘reader, pay attention - you will enjoy yourself’ as one of the very first novelists, Lucius Apuleius, wrote sometime in the second century) there’s a new Lindsey Davis novel.

A Comedy of Terrors [Hodder] is the latest outing for Flavia Alba, the doggedly determined (and British, sort of) private investigator in the man’s world (and many of the men are total jerks) of Ancient Rome circa AD89. I have to admit that I had my doubts when Flavia first took centre stage from Lindsey’s original Roman gumshoe (gum sandal?), Marcus Didius Falco, but I am now a dedicated fan as she follows in her adopted father’s footsteps down those mean via. In A Comedy of Terrors it might be Saturnalia, but that doesn’t mean a very merry time will be had by all, especially those allergic to nuts or practical jokes in really bad taste.

If you prefer a more up-to-date historical mystery, but still far enough in the past not to give you nightmares, the gold standard has surely been set by Andrew Taylor, whose latest, The Royal Secret [HarperCollins] paints a technicolour picture of the intrigue, sights, sounds and smells (particularly the smells), of Restoration London in 1670. This tale, continuing the careers of the adventurous young (female) architect Cat Hakesby and the more uptight James Marwood in one of the most turbulent periods of London’s history.

Not that some things ever change and the scene where Marwood has to help a very drunk companion down The Strand...well, we’ve all been there. And then, as now, relations with the rest of Europe are strained - to say the least - and perhaps it’s best to be wary of Dutchmen bearing gifts.

Between 2007 and 2013, David Downing wrote six exceptional historical spy novels each named after a Berlin station during and immediately after WWII, his hero being John Russell, an Anglo-American journalist and former communist with a German wife and son, which meant he could (and did) spy for just about anyone. After a gap of eight years, Wedding Station [Old Street Publishing] - Wedding being a district of Berlin - gives us Russell’s back story as a newspaper crime reporter in February 1933 as the Nazis have taken power and the Reichstag burns.

As law-and-order now seems a matter for thuggish SA brown shirts rather than the police, Russell is drawn into the murder of a young male prostitute, a missing girl with communist party loyalties, the suspicious death of a genealogical researcher and a disappearing (Jewish) astrologer. In this Berlin, Russell is not undercover, or a spy, but doing a policeman’s job because the police cannot or, for political reasons, choose not to. There is a staggering amount of detail, all of which I am sure is accurate, about the street plan and transport systems of pre-war Berlin - perhaps too much information - and the book lacks the suspense of those set in the latter days of the war, particularly the outstanding Potsdam Station. Still, it is very good to see John Russell back in action, a man with a dangerous job in a dangerous place at a very dangerous time.

Reading Jo Spain’s The Perfect Lie [Quercus] I got the same feeling I get when watching a TV thriller where characters go into a darkened room or cellar, knowing that there’s something nasty there and always feel like screaming “Put the bloody lights on!”. In the case of The Perfect Lie it is more a case of why didn’t they ask that at the time? Because if they had, things might have been clearer. But that is not the point, because this is a thriller which sets out to bamboozle the reader from the start and many a reader will happily go along with it, suspending a large amount of disbelief as the author uses every trick in the book to string out the suspense by withholding information and deliberately confusing the timeline, plot twists being more important than in-depth characterisation or motivation.

Curiously, or perhaps not, this is the third novel of ‘domestic suspense’ I have read this year (so far) where a female protagonist is motivated or haunted by a missing, or murdered sister. It stands out by being set in America, though the author is Irish, and whilst certain well-known Irish authors have had great success in writing credible American settings, The Perfect Lie (which has an Irish protagonist) tries a little too hard, almost as if it had been translated into American.

The initial question posed in Charlotte Northedge’s debut novel of domestic suspense The House Guest [HarperCollins] is which of the two main characters is the more bonkers: Kate, the disturbed young woman struggling to survive in London whilst searching for a lost sister who joins a ‘life coaching’ group of middle-class women, or Della, the alpha-female ‘life coach’ who runs it? It soon becomes clear that Kate fancies Della’s successful lifestyle, house and family (Della is a sort of unsympathetic version of the Amanda character from the wonderful sitcom Motherland), and the wannabe house guest gets her wish suspiciously easily.

As Kate worms her way in to Della’s life (mostly by being remarkably passive and unaware), it seems as if we are in for a classic cuckoo-in-the-nest tale, but then things twist and we might be looking at a Handmaid’s Tale scenario, though minus the religious fanaticism. It is difficult to believe that Kate, a 25-year-old university graduate, initially accepts her fate which involves in being isolated, though not actually restrained, alone in a villa in the south of France for nine months (spoiler alert), without trying to escape or pick up more than two words of French, and it is not surprising that her attempts at finding justice as she sees it, are fairly inept and doomed from the start. As a thriller, The House Guest may have its flaws, but it does explore interesting themes of loss, exploitation of the weak by those with sharper elbows, metropolitan middle-class anxieties and, above all, motherhood.

Dark Moon Rising

With due deference to Mr Aldrin, there is already a considerable buzz about The Apollo Murders to be published by Quercus in October.

Houston certainly sounds to have a problem in this thriller set partly on the far side of the Moon in 1971, by American astronaut Chris Hadfield, though it is not, of course, the first murder mystery to have been set there.

Back in 1990, the late, great Reginald Hill produced the whimsical novella One Small Step featuring his famous detective duo Dalziel and Pascoe investigating the murder of a French astronaut. You knew it was science fiction because it was set in the future - in 2010! - and that it was also fantasy as the astronaut was part of a space programme run by the unthinkable ‘Federated States of Europe’.

Until normal service resumes,

The Ripster.

3 comments:

Spurs! Some of us remember the glory days of Danny Blanchflower.

(No need to publish this one.)

Love the discussion of the le Quex novel. I too had heard about it, but had never read it ... I love the idea of the alternative First World War being won or lost in the public bars of Suffolk. Must read it.

Le Quex, of course, was a bible for MI6 between the wars, (a bit like Le Carré later) to the point where its head was nicknamed Quex - as was the German Field Marshal Blomberg who was known as "Hitler Boy Quex".

Re Chris Hatfield

I am pretty sure the multi talented astronaut is a Canadian. One

of the Colonies, you know.

Chris Wallace

Canadian

Post a Comment