There are many good reasons, of course – not least the moral ambiguity and jeopardy that war provides – but the real reason, for a writer, is that one is drawn to it.

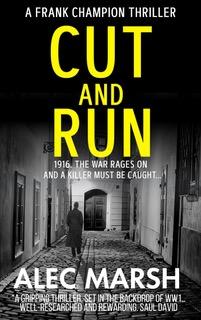

And in my case that began a long time ago with a handful individuals, who led me on a path that would end with Cut and Run, my new crime thriller about an injured ex-serviceman named Frank Champion who goes to back to France in 1916 to solve a murder.

I’ll start with the maiden aunts. Did you ever have a maiden aunt? They don’t make them anymore, not in the sorts of numbers that they did back then. I had three – sisters – who lived in Edmonton in North London in a house without, seemingly, a television set and where the dining table was always laden with the sort of high tea that an Edwardian would have recognised – and relished.

Olive, Dorothy and Alice were unmarried because their would-be husbands had been killed in the First World War; young men who were part of Vera Brittain’s famous lost generation, following a conflict which claimed the lives of one in four junior officers. What’s more, for my three maiden aunts, that lost generation included their elder brother, whose photograph was framed surrounded by the flags of the allied nations, and proudly displayed on the wall on the upstairs hall.

He never came home, was all Olive would say, when I did what a five-year-old like me would do and ask about him. I dare say it was conveyed with what we would now regard as resolute understatement, but that’s what people were like then.

Another first-hand recollection of the world of the Great War came from my grandmother who remembered seeing the Tommies going off to fight on the trains. In my memory they are waving through at the windows at her. One of her strongest recollections was being called into the playground and told to told by the headmistress that at 11 o’clock precisely that the war would end and the guns would fall silent across Europe. The joy and import in her words travelled through time.

Then there was my grandfather – my dad’s father, who fought and was injured in the war, but survived. He was in the horse artillery and there are pictures of him in the 1970s carrying around an enormous hearing aid. A decent man, I’m told, but hard to know, my father said. What the experience taught him was that the most important job of a junior officer was to protect their men against the senior officers. Which would be hilarious if it wasn’t so tragic. And surely it informs the outlook of my book’s protagonist Frank Champion.

The final – and probably the most important – personal interaction that informs the backdrop to Cut and Runis my meeting with a Great War veteran Smiler Marshall who died in 2005, before his 109th birthday. I interviewed him in 2000 when he was 104.

A farrier by trade, he had joined the Essex Yeomanry after shaking hands with Lord Kitchener at a recruitment event in 1914 was a cavalryman who would fight at the Somme – and much else, serving until 1921. During our conversation, in between singing wartime songs, he told me, with tears in his eyes, about the horrors of what he’d seen, about going out into no man’s land and seeing his mates killed. He left me in no doubt that war was a dreadful, profound waste of life.

Smiler was one of the last Great War veterans to die. He was followed by Harry Patch who died in 2009 at 111. ‘When the war ended, I don’t know if I was more relieved that we’d won or that I didn’t have to go back,’ Patch recalled in 2004. ‘Passchendaele was a disastrous battle—thousands and thousands of young lives were lost. It makes me angry. Earlier this year, I went back to Ypres to shake the hand of Charles Kuentz, Germany’s only surviving veteran from the war. It was emotional. He is 107. We’ve had 87 years to think what war is. To me, it’s a licence to go out and murder. Why should the British government call me up and take me out to a battlefield to shoot a man I never knew, whose language I couldn’t speak? All those lives lost for a war finished over a table. Now what is the sense in that?’

But it happened and some 900,000 British and British Empire were killed in the process, out of around 20 million worldwide.

So before the slaughter and loss of the Great War recedes from our memories and the folklore of our shared culture, joining the Crimean, Napoleonic or the Seven Years war in the archive – I wanted to bring that world back. Because it’s only a few handshakes in to our past, a great-grandfather or a maiden aunt away. And that is but a blink in the eye in time.

Cut and Run by Alec Marsh (Sharpe Books) Out Now

March 1916, The Great War rages across Europe. In the British Army garrison town of Bethune in northern France, a woman’s body is found in a park. Her throat has been cut. Marie-Louise Toulon is a prostitute at the Blue Lamp, the brothel catering exclusively to officers of the British Army stationed in the area. Wounded ex-soldier Frank Champion is brought in to investigate the crime - to find the killer believed to be among the officer corps. But almost before his investigation gets underway another woman from the Blue Lamp is killed, her throat also cut. A third prostitute, meanwhile, has gone missing. Then two more bodies are uncovered, including that of a British Army captain who appears to have taken his own life with his service revolver. But all is not what it seems… Champion must face a race against time to save the life of another woman - at the risk of dying himself.

Cut and Run by Alec Marsh is published by Sharpe Books in paperback priced £8.99 and Kindle, priced £3.99. It also available in KindleUnlimited:

More information about Alec Marsh and his books can be found on his website. You can also find him on X @AlecMarsh and on Instagram @marsh_alec. You can also find him on Facebook.

No comments:

Post a Comment