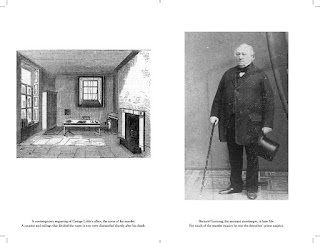

In November 1856 George Little, the chief cashier of Dublin’s Broadstone railway terminus, was found dead, lying in a pool of blood underneath his desk. The door was locked, apparently from the inside, and thousands of pounds in gold and silver had been left untouched on his desk. Was this a robbery gone wrong? A revenge killing? Or even suicide?

It was as perplexing a mystery as anybody could remember, and it led to the longest and most complex murder inquiry in the history of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Over the next seven months, more than half a dozen suspects were interviewed and taken into custody before the detectives finally succeeded in pinning down the man they believed responsible for the senseless killing.

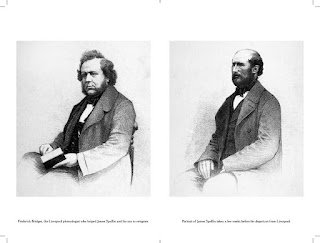

When I first came across a contemporary news report about this real-life murder mystery I knew straight away that I wanted to write a book about it. Both the immediate setting of a busy railway station, and the atmospheric surroundings of Victorian Dublin, were enticing. The crime itself was a genuine whodunit, and one that was not easily solved. There were twists worthy of an Agatha Christie novel, and dramatic sudden breakthroughs such as the recovery of a bundle of stolen money, just when the police investigation seemed to have ground to a halt. Then there was the surprise tip-off that led to the arrest of the prime suspect several months later, and a thrilling murder trial that gripped the nation. But perhaps the strangest episode in this tale is its unexpected epilogue, which features a scientist who believed that he could identify a murderer by analysing the shape of their skull.

The Dublin Railway Murder was a particularly lurid case in an era of sensational murders. No wonder, then, that every stage of the police investigation was followed eagerly by journalists on both sides of the Irish Sea. The detailed contemporary newspaper coverage provided me with invaluable source material, including verbatim accounts of the inquest and eventual trial.

These articles also included colourful details: eyewitness reports of the discovery of the murder weapon, and first-hand descriptions of the significant characters and locations of this drama. I also came across a pamphlet written, and privately published, by somebody who had befriended the main suspect and made notes of their hours of conversations.All this was more than enough raw material for a book. But then I paid a visit to the Irish national archives in Dublin, and made a discovery that transformed the whole story. In a dusty file, undisturbed for decades, lay hundreds of pages documenting the course of the police inquiry: transcripts of interviews with witnesses and suspects, letters between detectives and legal officials, and the minutes of confidential meetings.

There were even surveillance reports filed by the undercover agents who were given the task of discreetly tailing various suspects around the city.

This new information was a goldmine. It gave a totally different perspective on the story, revealing details of the investigation that the police had deliberately kept secret. It made it possible to deduce the precise chronology of the investigation, working out who spoke to whom and when. And, crucially, it allowed me to reconstruct entire conversations using the actual words of the people concerned, so that we can hear the authentic voices of the labourers, domestic servants, clerks and railway engineers who helped the police with their inquiries.

I wanted to make The Dublin Railway Murder read like a crime novel, but almost everything in it is based closely on the historical record – not just what people said, but where they lived, what they did for a living, and how they spent their leisure hours. It was often these incidental details that were most fun to research: what shops there were in a specific street, the weather on a particular day, even the romantic history of one elderly judge. Of course it is impossible to be absolutely accurate, or to recover the unadulterated truth about such a story, particularly at a distance of more than a century and a half – but the exceptional nature of the source material offers what I believe to be a uniquely detailed portrait of a Victorian murder inquiry.

The Dublin Railway Murder by Thomas Morris (Harvill Secker) Out Now.

A thrilling and perplexing investigation of a true Victorian crime at a Dublin railway station. Dublin, November 1856: George Little, the chief cashier of the Broadstone railway terminus, is found dead, lying in a pool of blood beneath his desk. He has been savagely beaten, his head almost severed; there is no sign of a murder weapon, and the office door is locked, apparently from the inside. Thousands of pounds in gold and silver are left untouched at the scene of the crime. Augustus Guy, Ireland's most experienced detective, teams up with Dublin's leading lawyer to investigate the murder. But the mystery defies all explanation, and two celebrated sleuths sent by Scotland Yard soon return to London, baffled. Five suspects are arrested then released, with every step of the salacious case followed by the press, clamouring for answers. But then a local woman comes forward, claiming to know the murderer....

You can find more information on his website. You can also follow him on Twitter @thomasngmorris